When the Archives Reopen

When the Card Isn’t There: What the paper trail says—and where the story actually lives

This essay continues When the Archives Go Dark, written at the moment a federal government shutdown interrupted my request to the National Archives and left a century-old question suspended in midair. The first essay explored the pause; this essay begins when the lights come back on.

What changed wasn’t the past, but my understanding of it.

The card I expected to find never appeared—not because it was lost, but because it no longer belonged where I was looking. With the archives reopened and the guidance of archivists in College Park and St. Louis, I learned something essential: the absence of the record I was seeking is not an archival failure.

It is, in fact, the answer.

The Record Series That Framed the Search

The 3×5 index cards I described belong to a specific record series:

Record Group 120, Entry 568

“Name File of Dead and Severely Wounded Casualties of Infantry Divisions in the American Expeditionary Forces, 1918.”

Archivists at College Park conducted a search of this series for soldiers of the 165th Infantry wounded on October 15, 1918.

No card for my great-grandfather was found. At first, this was disappointing news. Another locked door.

But as archivist Martin A. Gedra explained, this particular file contains cards only for those who were killed or whose wounds remained classified as severe.

That distinction matters.

Reduced to a word. Filed by fate.

A Downgraded Injury

My great-grandfather was initially reported—by the Army and by contemporary newspapers—as Severely Wounded in Action.

Later records, including his New York State World War I Service Abstract and interment documentation, show that this classification was officially amended to Moderately Wounded.

Once that downgrade occurred, his record no longer belonged in the “dead and severely wounded” casualty file.

In other words, the card I was searching for was either removed or never meant to be there in the first place.

Why Downgrades Happened

This kind of reclassification was not unusual in the final weeks of World War I.

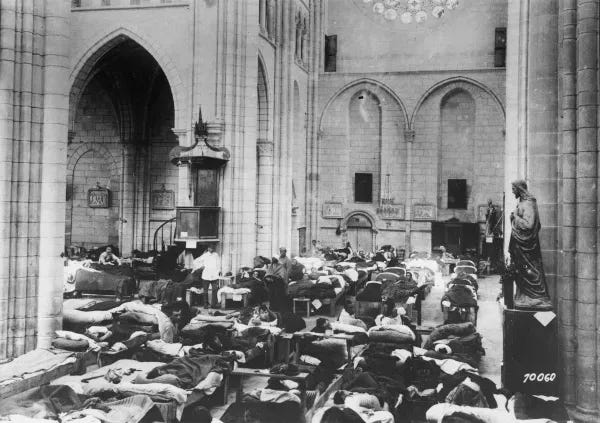

Casualty reports near the front were made quickly, often with limited information. Soldiers wounded during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive—particularly in October 1918, when evacuation routes were strained and hospitals overwhelmed—were frequently listed as severe until their condition stabilized.

Once a wounded soldier survived the critical period, avoided amputation or fatal infection, and could be returned stateside, his status was often revised administratively.

This did not mean his injury was minor.

It meant it was survivable.

And survivability changed where the paperwork went.

Some stabilized enough to live. Never enough to forget.

In 1918, words like severely, moderately, and slightly wounded were part of a rough triage vocabulary—not a moral judgment. Near the front, a man might be labeled severely wounded when death was expected. As he stabilized, that same wound could later be reclassified as moderate, signaling survival even if pain, weakness, or disability would follow him home.

For my great-grandfather, the downgrade almost certainly marks the moment when the Army stopped expecting him to die of his wound, but not the moment when the wound stopped shaping everything that followed in his life.

Where the Record Does Exist

Archivist David R. Hardin, Supervisory Archivist at the National Archives at St. Louis, helped redirect my search to the place where surviving soldiers’ wounds were ultimately documented—not in battlefield casualty cards, but in benefits files.

Because my great-grandfather did not die in service, he never had a Burial Case File (later called an Individual Deceased Personnel File, or IDPF).

Instead, his service-connected injuries were tracked by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Specifically, his records are filed under a Deceased Veterans Claim File:

VA File No. XC-158221

These files were created to administer disability ratings and benefits. They often include medical evaluations, hospitalization summaries, disability determinations, and correspondence explaining how an injury affected a veteran’s postwar life.

This is where the Army stopped speaking in shorthand and started speaking in consequences.

From Triage to Pay Stub

After the war, agencies that became today’s VA attempted—imperfectly—to translate damage into percentages.

A 25% disability rating, like my great-grandfather’s, placed him in the middle ground: officially partially disabled, still considered employable, yet permanently impaired in ways the government acknowledged were the result of military service.

That percentage did not depend on whether an early report called his wound severe or moderate. It rested on what doctors determined his body could no longer do.

On paper, moderately wounded sounds manageable.

In family memory, it meant he was never really well again.

What This Means

The question that started this search—why was his injury downgraded from severe to moderate?—was never going to be answered by a single card.

It lives instead in a longer paper trail: one that follows a wounded soldier from battlefield, to stabilization, to demobilization, and into civilian life with a 25% service-connected disability.

The downgrade did not erase his wound.

It rerouted his story.

What Comes Next

The casualty card told me how the Army first understood my great-grandfather’s wound. The file I’m now seeking may tell me how he lived with it.

The next step is a request to the Department of Veterans Affairs for the claim file, where a battlefield injury was translated into medical judgment, disability percentages, and the limits of ordinary days.

I don’t know exactly what it will contain, or what it will leave unsaid.

But I hope it helps me better understand the shape of his injury, how it followed him home, and how it quietly shaped the rest of his life.

It is the next door I’ll knock on.

📚 Sources & Suggested Further Reading

National Archives & Record Groups

Military Medicine & Casualties

Veterans’ Benefits & Disability Ratings

Fascinating!

Thanks for clarifying those terms and explaining what you found about the papertrail.